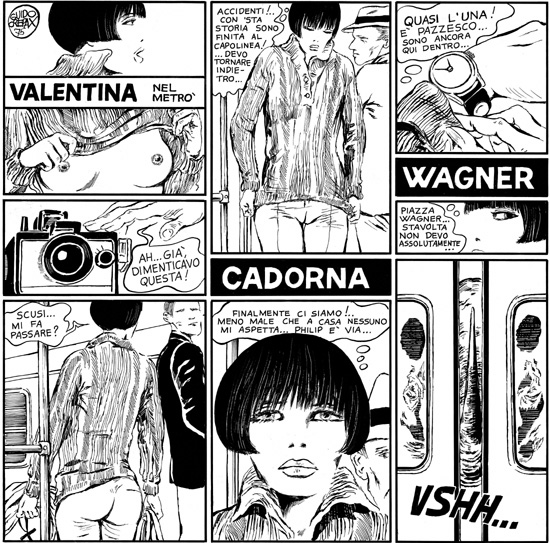

Valentina is an Italian comic strip series, created in 1965 by the Italian artist Guido Crepax and concluded in 1996. Originally a minor character working for the comic hero Neutron, Valentina became the sole protagonist of the series in 1967. Guido Crepax - Valentina - Funny Valentine- Episode: New Orleans Function - page 3, 1967 Posted By Maurizio Scudiero 3397 Views, 9 Comments + Valentina. Artist: Guido Crepax (Painter) Media Type: Pen and Ink: Art Type: Other: For Sale Status: Views: 3368: Comments: 2: Added to Site: 1/15/2012.

- Valentina Crepax Taglio Capelli

- Guido Crepax Valentina Spacesuit

- Valentina Crepax Wikipedia

- Valentina Crepax Frasi

- Valentina Crepax Giornalista

- Valentina Crepax Serie Tv

An elegant, sophisticated erotic dream for men, a symbol of independence, fascination and seduction for women, Valentina is the star of a large 'anarchic and emotiona' exhibition in Rome (30 May-30 September, Palazzo Incontro).

The comprehensive show, curated by Archivio Crepax and Vincenzo Mollica, puts the spotlight on a figure who’s been called one of the most complex and sensual women in Italian comics– and justly so. It follows her from her origins in the mid-60s to her latest incarnations.

Over time, we’ve got to know everything about her, from the details of her identity card (Valentina Rosselli; born Milan 25 December 1942, resident at 45, Via de Amicis, single, 1.73m in height, black hair, pale eyes, no distinguishing features) to the sources that inspired the artist Guido Crepax when he set out to create Valentina (they include the actress Louise Brooks) as well as intimate moments from her life, such as the birth of her son Mattia in 1970.

With her famous black bob and camera (which she takes everywhere), Valentina is a sensual Milanese photographer with a cat-like figure that – as an independent woman – she shows off without too many inhibitions. A character perpetually balanced between imagination and reality, our heroine has never hidden her neuroses, her excesses and her obsessions, as well as the fact that she’s often the victim of nightmares and hallucinations, features that have become the lifeblood of the development of her comic book stories.

The exhibition immerses visitors in her world: it’s the complete Valentina experience and doesn’t spare coups de théâtre or the more fun, entertaining side of the character. Life-size silhouettes of Valentina guide us through the many themed sections: Valentina’s origins, her relationship to her time (fashion, photography and advertising), the cities that have been the backdrop to her adventures (New York, Paris, Prague, Berlin, among others). Then there are sections on the more dreamy and hallucinatory aspects of the comic, as well on the relationship of the character to music, cinema and literature. Plus there are over 120 original artworks selected from the 2600 that Crepax made featuring her.

Her creator died in 2003 and the exhibition includes a large section recreating both the real and the imaginary sides of his studio. There are his sources of inspiration, extensive documentary material and a range of filmed interviews with both Crepax and with major artists and critics talking about his work.

Valentina Movie

22, Via dei Prefetti, Palazzo Incontro, Rome

30 May – 30 September 2012

Valentina Crepax Taglio Capelli

Add comment

Last On Vogue

Valentina Rosselli was a Milanese photographer born in 1942, fashionable, a communist. She first appeared as a side character in the 1965 story 'The Lesmo Curve', which largely focuses on the character Neutron, a.k.a. Philip Rembrandt, an art critic with the mysterious power to stop humans or objects via his gaze. The two characters became lovers and Valentina assumed the role of protagonist in subsequent stories, which were, at first, genre adventures reminiscent of American newspaper serials and mixing science fiction, horror, and intrigue, and later on, grew into tales more concerned with the reality (and the fantasy) of her domestic life.

Valentina's rich dream/fantasy life often features eroticism and a predilection towards s&m, and that last element is probably the main source of notoriety for Guido Crepax, Valentina's creator. Previous to the Complete Crepax series, currently ongoing annually from Fantagraphics (the fourth and latest volume of which I am mostly concerned with here), the easiest English translations of Crepax's work to find were his adaptations of such titles as The Story of O, Venus in Furs, and the Marquis de Sade's Justine. Other translations have appeared in English, primarily in the late '80s and early '90s from Catalan Communications, NBM (via their Eurotica imprint), and a handful of stories in Heavy Metal, but they have been long out of print, and represent only a patchwork of a larger whole. The heavy focus on the erotic aspects of Crepax's work has made knowledge of him in English-speaking countries too limited. He is a master of the comics form, creating beautiful drawings within a framework of innovative page layouts and panel breakdowns.

The Complete Crepax 4: Private Life offers an excellent entry point to Valentina's extended suite of comics; it includes the character's first appearance, as well as a number of longer, less genre-heavy stories that still feature the mystery, horror, and Surrealism that should make Crepax better known. It is also lighter on the sexuality and s&m elements that might turn off some readers. Valentina (the main focus of this volume) offers so much more than what is implied by the erotic label Crepax is attached to. The best analogy I can come up with is to Jaime Hernandez's Locas stories from Love & Rockets; Valentina is Crepax's Maggie.

'A single creator's decades-long suite of comics of varying lengths, which starts out heavily based in genre, and features a psychologically rich female protagonist who ages over the course of the work and whose sexuality is prominent aspect of the narrative': This could describe both the Valentina stories and Locas. There are of course differences. Jaime relies much more heavily on an ongoing supporting cast of characters. Hopey is a more of a second protagonist in Locas than Valentina's lover Phil is in Crepax's stories. Phil appears often, but the stories are almost never about him (as far as I have read). Both artists continued to mix genre elements into their stories, but Crepax held on to his throughout the suite more than Jaime has. The early 'Rockets' of Love & Rockets are rarely, if ever, a topic in the main Locas stories, while Crepax continued to use elements of mystery, horror, fantasy, and science fiction. Genre elements are not absent even in the more domestic stories in this volume.

Guido Crepax Valentina Spacesuit

Valentina Crepax Wikipedia

From interviews, the artists' relations to their protagonists seem to be of a similar nature, one where the characters mix what the artists are attracted to with elements of themselves. You see the artists growing along with the characters over the course of years. Interestingly, while Hernandez has gotten more and more clean-lined and minimal, Crepax moved over the course of his life to a scratchier, lighter style, utilizing numerous small lines (especially prominent in his later literary adaptions seen in earlier volumes of this series).

For both artists (and their protagonists) sexuality (and eroticism) is an important aspect of the comics. Maggie's (and Hopey's) sexuality is a frequent topic of the Locas stories and Jaime never shies away from showing sex, but it is a sexuality of relationships and drama. In Crepax, the sexuality is more explicit (though even he is subtler about actual physical acts), embedded in a Surrealism of dreams and the subconscious come to life that suffuses his stories. That is not to say I would classify these stories as pornography (though the term is often used in reference to Crepax). I don't think Crepax made these Valentina stories exclusively for erotic titillation. Valentina is a fully realized character and her stories are not just thin plots on which to hang sex.

Crepax's fellow Italian comics artist Milo Manara provides a good point of comparison. Manara's stories are vehicles for him to draw naked women (who all look the same, and seem to share only one facial expression) engaged in various sexual acts. The plots exist to create the situations that I guess interest Manara, or at least what he knows his fans want.

Crepax's work is less pornographic even than the dozens of 'good/bad girl' comics that one can find while browsing the new releases on comiXology. They seem to exist solely for the purpose of inspiring a cover image featuring a busty woman in skimpy clothes (that always seem to be a superhero artist's received idea of what is sexy), rather than for any other visual or narrative reason.

Crepax is more than that. Clearly he had a heavy interest in s&m, but the images in these comics are not hardcore. It's almost as if his primary attraction to the topic is via drawing contorted figures (sometimes bound or gagged). I should note that I don't personally have an interest in s&m; I say that not as a disclaimer but to point out that my interest in these comics exists despite this particular focus of Crepax's, not because of it. You can enjoy these comics as stories without any investment in all the aspects of the eroticism present.

Still, there is seduction in Crepax's work. It is not about the sex or the naked bodies, but in reading these comics and stopping to marvel at a line, a panel, a layout, a sequence of panels. There is so much formal beauty to Crepax's work. Having spoken generally about the stories, it's worth looking at a few particulars of the art in this volume.

This early sequence from the first story shows Crepax very early in his career, already showing a sense of design and innovation that seems very different from American comics of the '60s. We see an early example of one of Crepax's other most famous traits, the fragmentation of scenes into many panels. This sequence depicts the first meeting of Valentina and Philip Rembrandt, and already you can see his strong sense of page, utilizing the airport background to include arrows for directing the reader through the panels. The drawing style, with its brushy lines of all sizes and expressionistic rendering, reminds me more of modern art than of other comics of the period. This scratchy dry brushwork quickly disappears in Crepax's style in favor of more bold solid blacks and cleaner lines, but returns later in conjunction with his scratchier line work.

In 1966's 'Ciao, Valentina', we see the bolder, cleaner style Crepax shifted into as well as a more extended example of fragmented pacing. By 1972's 'Valentina the Fearless', the line work has gotten less bold and the fragmentation has gotten even more extensive, paced out longer, shifting focus around the scene more often, and offering more metaphorical readings. (This scene seems to depict what may be Valentina's first sexual appearance, in a very restrained way.) Crepax frequently focuses on small aspects of people and rooms, especially hands, mouths, and eyes.

Valentina Crepax Frasi

Sometimes Crepax's metaphorical imagery is perhaps a little too on the nose, but no less captivating to behold on the page, like this page from 'Valentina's Baby', a strikingly simple page with an obvious reading, borne out on the next page when Valentina shows up pregnant. What follows is a phantasmagoria of Valentina and Phil's subconscious thoughts during her labor and childbirth, featuring among other imagery, Valentina wrapped by an octopus (undoubtedly a reference to Japanese erotic prints) and slowly drowning before extricating herself from it (cue next page when the birth is over).

Crepax is not afraid to go self-referential, and occasionally even metafictional. 'Valentina the Fearless', from 1972, features a number of fantasy sequences where Crepax pastiches a variety of his comic-strip influences through the lens of Valentina's reading. Early on, as a child, she dreams in Little Nemo-esque dreamscapes. As she ages, she places herself into the role of Dale Arden from Flash Gordon, then in short adventures with The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician before she grows up enough, one imagines, to stop reading the comics. Another story in this volume also features an appearance by Huge Pratt's Corto Maltese (echoing a recent Corto Maltese reprint from IDW which features a Valentina cameo). The final story in this volume, 'Private Life', is basically an unseen narrator asking Valentina questions about her life for the 'readers,' leading to Crepax drawing a series of new panels showing events from previous stories, offering a kind of recap of stories from this volume, from earlier books, and from some that have not yet appeared in the series.

This is one of the downsides for new readers (and even those familiar with Valentina): the gaps in the chronology. Fantagraphics chose to organize the series thematically, breaking up the chronology of the publication, and in the case of the Valentina stories, the chronology of the character's life. This choice creates unusual time jumps and referential omissions. The latter is particularly important for the background genre elements in some stories. The Complete Crepax 1 starts out with 'The Subterraneans', an early Valentina story (the second, perhaps?) from 1965, where Philip/Neutron is still ostensibly the protagonist, in which we discover the origin of his superpower as the ancestor of a race of humans who live under the earth. These beings are referenced a few times in the current volume but without having read the early volumes the context is a bit lacking.

Valentina Crepax Giornalista

One can understand the impulse to thematic organization, especially as it allows for the books to feature Crepax's work from a variety of periods (the previous three volumes all featured a mix of Valentina stories and later works such as the many literary adaptations he made), but the lack of publication context can be frustrating in terms of piecing together the chronology. Volume 2 features a 'Publication History' section, but none of the other volumes do. Thankfully, Crepax from the beginning had the habit of signing all his pages with a year, which not only provides context, but also exposes places where stories were clearly edited for later publication. Seeing the work across the years all at once like this showcases the way Crepax's style evolved during his lifetime, but I'm tempted to make my own chronology so I can read at least the Valentina stories in order. (I also expect the thematic organization will allow Fantagraphics to gather all the previously mentioned erotic adaptions in to a single volume, perhaps volume X.)

Valentina Crepax Serie Tv

The volumes themselves, large hardcovers, beautifully showcase Crepax's art, the lines of which earlier, smaller editions often blurred and blended. I have some recent French editions from Actes Sud that are smaller in size and not nearly as nicely printed. Comparing the same story across the editions reveals how the Fantagraphics edition brings out the detail of the linework. I only noticed a few pages in this volume of lower quality, I assume resulting from a lack of access to the original pages. Unlike so many comic artists, Crepax's family seems to retain ownership of his work and that clearly pays off in access for this edition, which features an interview with Crepax from 1980, a biography, and a few essays on some of the stories (including from a few TCJ contributors). The price tag for these volumes is a bit high, but for over 400 pages of quality reproductions from a master of the art, it is well worth it.