About Vidyadhari

Welcome to the official website of ‘Vidyadhari School of Music’. We are proud to be considered as one of the best and finest music schools in Visakhapatnam having multiple branches in different locations as well. You would like to know why? Read further!

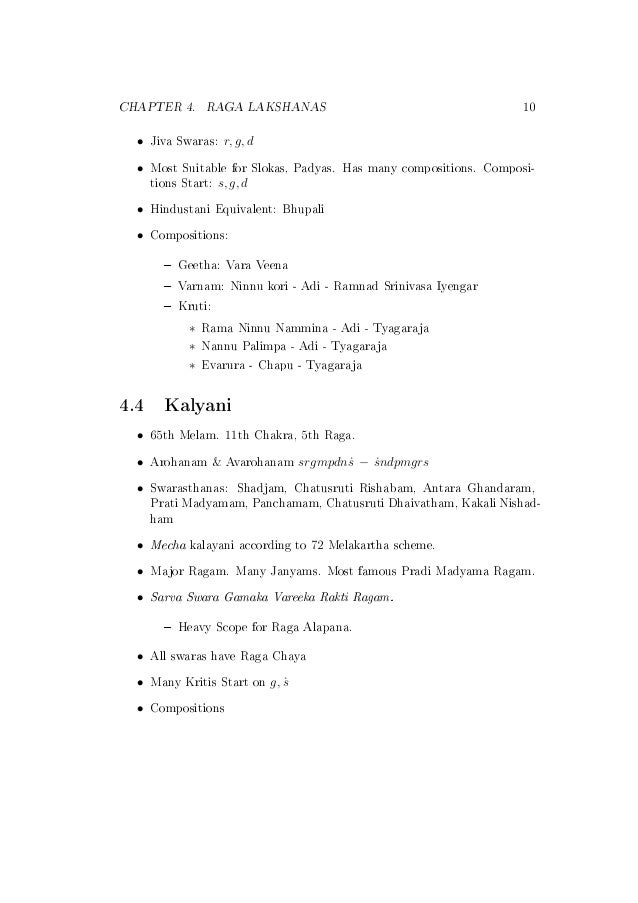

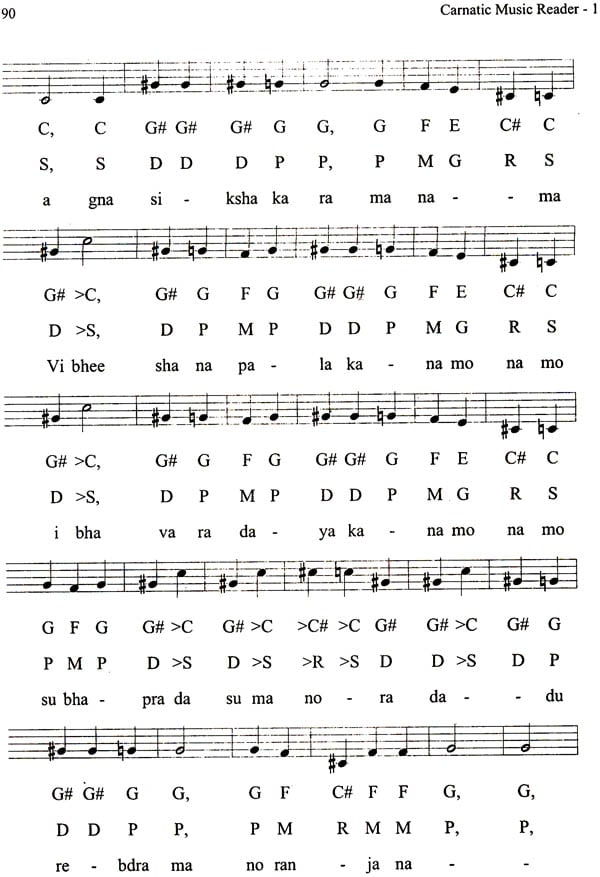

Carnatic Music is ruled by 7 octave musical notes. These Sapta Swaras are believed to have originated from “Dumru” (Musical Instrument) of Lord Shiva. 7 musical notes (Swaras) are the following: Sa – Shadjama (Tonic). In this section I try to present the carnatic music notation for few phrases of Telugu movie songs. The notation used is as follows: Symbols S, R, G, M, P, D, N indicate normal notes.

How Many Ragas Are There In Carnatic Music? - UrbanPro

Read more

Read moreWe have an experienced and renowned staff for teaching Carnatic Vocal. Vidyadhari School of Music has 6-level schedule for training our students in Carnatic Vocal. Refer our Courses page for more details on all the six levels and also, on Advanced Learning Programs.

Read moreENROLL NOWAt Vidyadhari School of Music, Violin is taught with a vision to ensure the bright career of the learner. We are proud to say that we have students from our school performing in various concerts at a bigger scale.

Read moreENROLL NOWVeena is being taught by the one of the renowned Veena artists, a senior most faculty member of Vidyadhari School of Music.

Read moreENROLL NOWWe have an excellent young Guru for Mridangam, who has performed along with many legendary artists and well known singers. He is such a perfectionist who makes sure that the learner gets perfection with every bit and note.

Read moreENROLL NOWAt Vidyadhari School of Music, we have a dedicated teacher who exclusively teaches the theory subject. Having theoretical knowledge is very essential and it is a mandatory subject for clearing exams such as Certificate Course, Diploma, and M.A. in Music etc.

Read moreENROLL NOWIndian violin

To the ear of the western violin player Indian music, and perhaps the Indian violin in particular, is one of the most exotic and mysterious of sounds. And this is not merely superficial, for the more closely you examine the complexity and discipline of the Indian Classical tradition, the more mysterious and baffling it becomes.

There are two main branches of classical music in the Subcontinent; the Carnatic or South Indian, and the Hindustani or Northern. The two styles diverged around the 14th Century AD, but have common roots dating back to the 4th Century BC. The biggest difference between Indian and Western Classical music is that the former is based very largely on improvisation, with emphasis on the creativity of the performer rather than on the exact reproduction of a composer's work.

Raags

The performer must work within a rigorous and complex framework of scale and rhythm; it is the ability to be inventive within these restrictions that marks out the quality of an artist. In Carnatic music for example there are 72 main scales or Melakartas, each of which has its own set of ornaments and Gamakas (grace notes); and 35 principal rhythms or Talas. A performance or Raag (often called Raga), which may last for several hours, will specify the use of a combination of certain melakartas and talas, and will have a simple melodic line, often from a religious or folk song; this however may not appear until late in a piece, and most of the performance is spent in examining and elaborating the particular mood and feel of the Raag. Raags were originally based mainly around the vocal tradition, and are not instrument-specific; indeed it is remarkable to hear the similarity in tone and ornamentation when comparing vocal and violin performances of a raag.

Probably the most important melody instrument is the Sitar, a plucked stringed instrument whose characteristic whining and 'zinging' sound comes from the many sympathetic drone strings, and the ability to bend the strings sideways, thus sliding the note. An instrument called the Ravanastron is said to be the earliest ancestor of the fiddle, in that it was the first stringed instrument played with a bow. King Ravana of Ceylon is said to have invented the bow, and the instrument he used it on was named after him- the date for this is either 3000 or 5000 BC depending on what source you believe. Other stringed instruments include the Tambura (a four-stringed drone instrument, the Sarod (a small sitar), the Surbahar (bass sitar) and, from Hindustan, the Sarangi.

The Sarangi: A hundred colours

The Sarangi is a strange and ancient relative of the European violin which is both highly expressive and extremely difficult to play. Its name means 'a hundred colours', indicating the range, depth and subtlety of its voice. The instrument expresses, according to the late Sir Yehudi Menuhin, 'the very soul of Indian feeling and thought'. It has an important and growing role in North Indian music, but has largely died out in the south.

It is said that the Sarangi originated in ancient times when a weary travelling hakim (doctor) lay down under a tree to rest in a forest. He was startled by a strange sound from above, which he eventually found to be caused by the wind blowing over the dried-up skin of a dead monkey, stretched between some branches. With this unlikely event as his inspiration, he proceeded home and constructed the first sarangi

It is squat and box-like, carved from a single piece of hardwood (usually Indian Cedar), with three gut melody strings (tuned do-so-do) and a baffling array of up to 40 metal tarab (sympathetic strings). The body has a goatskin face on which rests an elephant-shaped bridge of ivory or bone. The Sarangi is held vertically, neck uppermost, and the strings are stopped not with the fingertips but with the backs of the nails. A characteristic feature of sarangi playing is the very smooth meend (glissandos) and gamakas (oscillations around the note). Talcum powder is used on the palms of the hands to facilitate easy sliding on the neck.The heavy bow is held with an underhand grip, the first and second fingers placed between the hair and the stick. Among the current masters of the instrument are Pandit Ram Narayan and Ustad Sultan Khan; they have achieved conspicuous success despite a general decline in the fortunes of the sarangi, brought about both by its poor image (associated as it is with the accompaniment of dancing-girls), and by competition from the considerably sturdier and less troublesome harmonium.

Besides the classical sarangi described above, there exists a whole extended family of instruments either called by the same name, or structurally very similar, across the whole of North India, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Indian violin

The violin may have been introduced to India around 1790 by military bandsmen in the East India Company, many of whom were Irish. BaluswamiDikshitar (1786-1859) learned the instrument from the army bandmaster at Fort St.George in Madras, and developed new playing techniques to suit Carnatic music; he became court musician in Attaiyapuram. It has also been suggested that the violin came somewhat earlier, brought by Portugese Christian missionaries, and taught to converts for use in church services. Either way, the instrument was quickly found to be ideal for use in Indian classical music, with its closeness in timbre and range to the human voice. The initial Irish connection is supported by the name of one of the earliest prominent Carnatic violinists, referred to as 'Fiddle' Ponnusami. There are also examples of Irish fiddle tunes such as Rakes of Mallow which were adapted to the Carnatic tradition, along with Sanskrit words and titles (in this case Vande Minakshi)

In India the violin is played sitting cross legged, the instrument pointing to the ground with scroll resting firmly on the ankle of the right foot. This allows the left hand to slide freely up and down the neck, without any need for the instrument to be supprted by hand or chin. Traditionally fingering is based around the middle finger (which slides up), and the index finger (which slides down); these slides or portamenti, called meend in carnatic music, are sometimes facilitated by oiling the fingers. Open tunings in fifths, such as DADA or FCFC are commonly used in order to incorporate the drones which are such an important part of Indian music. The bow is held more in the folk than western classical style. Vibrato is not used as in Western music, though there are slow, deliberate oscillations (andolan) and faster oscillations called gamak.

The aim of tone production is to imitate the Indian singing style. Unlike in western violin playing, powerful projection is not required.As well as tuning in fifths, violinists often tune down a tone, giving a more mellow sound.

Ornamentation in Indian Violin

Ornaments or Grace notes (sparsha svara or krintan in Hindustani, Gamakas in Carnatic Knatic) are essential to achiving the correct sound of Indian violin. Whilst in western music ornaments are often considered to be an optional extra, in Indian music they are fundamental.

A 3rdC authority comments;

'A raga without subtle ornamented features is like a moonless night, a creeper without flowers, a river without water, a woman without jewelry'

Hindustani music alone has over a hundred categorised ornaments. Ornamentation marks were first codeified by Subbarama Dikshitar (grandson of the aforementioned Baluswami)- in his 1904 book 'Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini'. More recently a modern form of notation of ornaments was described by Smt. Vidya Shankar in her book 'The Art and Science of Carnatic Music'

The chief gamakas, as sumarised in Candida Connolly's book 'Indian Melodies for Violin' are the Kampita or shake (a gentle oscillation between two neighbouring notes); Nokku or descending pull (approaching a note with a slide from a semitone above); Pratyahata or strike back (a mordent, where a note drops to the next note down, then goes back up again); Sphurita or throbbing (here a note is repeated, and the second receives a mordent); Etrajaru and Irakkajaru are an upward and a downward slide respectively; Orikkai or snap is a little like an Irish cut or a klezmer kretschs- the note is interrupted by a flick of a higher note; Ravai or brief repetition (a note is preceded by itself and the next note down); and finally the Oddukal or note pushed aside (here a note is briefly interrupted by the previous note in the phrase)

Sargam Notation

The seven notes of a “major” scale are named or numbered- a bit like do, re mi. In the Carnatic notation system (called sargam), the names are, ascending the scale

Sa (Shadja- the sound of the peacock)

Ri (Rishabna-the sound of the ox)

Ga (Gandhara- the sound of the goat)

List Of Janya Ragas - Wikipedia

Ma (Madhyama-the sound of the crane)

Pa (Panchama-the sound of the cuckoo)

Dha (Dhaivata-the sound of the frog)

Ni (Nishadha-the sound of the elephant)

Carnatic Music Violin Notes Pdf

These names remain the same if the tonic is different, but they are not simply the numeric order in the scale. So if we are dealing with a pentatonic scale, the missing notes are removed from the naming system- for example sa, ri, ga, pa, ni, sa. (with the fourth and sixth missing).

Sharpened or flattened notes are distinguished by a number 1 to 3; 1 is flat, 2 natural and 3 sharp. For example if the the tonic (sa) is D, then Ri1 is Eb, Ri2 is E natural, and Ri3 is E#.

The scale may be different when ascending (arohana) or descending (avarohana).

Raags or Ragas

In the Carnatic system there are 72 principle raags or melakartas (“kings of the court”); also known as “major” scales, “parent scales” or janakas. These have all seven notes, both ascending and descending.

An example of a simple parent raga is G, Ab, B,C,D, Eb, F#, G. This raga (Mayamalavagaula) is traditionally the first one taught to students. It is what we know in the west as the Hungarian gypsy scale; it is the symmetry of the fingering which makes it particularly suitable for beginners.

Derived from these parent scales are “child scales”, in which one or more notes are missing- either ascending, descending or both. Since each parent can have many permutations of child scale, the total number of possible scales runs into the thousands. Each scale or raag has a name, and is associated with a particular mood, time of the day, season of the year, or even weather.

Examples include Bhairav (early morning); D, Eb, F#, G, A, Bb, C#, D; Bhupali (late afternoon); D,E,F#, A, B,D; Malkauns (late night); D,F,G,Bb,C,D); and Miya Malhar (rainy season); D,E,F,G,A,B,C,C#,D)

As with western modes, some raags are very popular, and have hundreds of compositions, whilst others exist more as little more than theoretical possibilities, and may only have a single composition

Ganesh and Kumaresh- a Carnatic violin duo

Tala

The tala is the rhythm. This also can be very complex to western ears- 17, 19, 7 and a half…The Carnatic method of counting to 8 (the Adi Tala), is by clapping the hand and tapping fingers on the knee. The count goes; clap (1), little finger (2), ring finger (3), middle finger (4), clap (5), turn- a clap with the back of the hand (6), clap (7) and turn (8). The first four parts are called the laghu or count. The subsequent front and back of the hand are one “turn”; so you get to 8 with a count and two turns. You could reach nine with a “count” of five, and two turns. Or seven would be a count of three, and two turns. Simple? There are just 105 different rhythms or talas to learn, so nothing to get worried about.

Indian Violin performance

A performance on Karnatic violin comes in three parts. The first is the Alap, a non-rhythmical improvisation of the particular scale or raag which has been chosen. Unlike in western music, there is no concept of chord changes, and the performance never deviates from the one scale. After the alap comes the composition (svarajati)- a fixed melody from an ancient repertoire of thousands. The bulk of the Carnatic compositions come from three composers from the 18th and 19thC; Tyagaraja, Dikshitar and Syama Sastri. Finally comes the kalpana svara (“creative notes”)- a rhythmic improvisation. This is the most exciting and challenging part of the performance.

Indian music first became widely known to the popular audience in the West in the late 1960's, when George Harrison, with the Beatles, visited India in search of alternative methods of mind-expanding spiritual enlightenment, and discovered, perhaps more usefully, the playing of sitar guru Ravi Shankar. Much musical cross-fertilisation followed, one of the most fruitful results being guitarist John McLaughlin's group Shakti, which included the violin genius L.Shankar.

L.Shankar with 10-string double violin

L.Shankar, as well as being a top player in both the Western and Carnatic classical traditions,uses his dazzling virtuosity to full effect in rock and jazz fusions with such artists as Peter Gabriel, Jan Garbarek, Frank Zappa, Talking Heads and fiddler Mark O'Connor. He has an astounding double-necked, 10-stringed electric violin giving him the full range of the string quartet- an instrument which would appear ridiculous and totally pretentious in the hands of almost any other violinist.

His brother is another famous violinist, Dr. L.Subramaniam (and it seems almost de rigeur for every Indian violinist to have a father, brother, sister and chiropodist who are famous and talented musicians). L.Subramaniam, like his brother, is a master of both western and Carnatic classical music, is a prolific composer, and is involved in East-West fusions, for example with Stephane Grappelli.

A recent newcomer to London is S.Harikumar, from Kerala in southern India; having studied with, among others, L.Subramaniam, he has developed his own Indian Jazz Fusion style, making good use of a technical mastery of staccato bowing techniques, and fluent playing up to the fifth octave.

S.Harikumar plays both 4-string acoustic and 7-string electric violins.

Harikumar

Contrary to the popular belief that all leading Indian musicians are men, one of the greatest of all pioneers of Hindustani violin in recent times is a woman, Dr.N Rajam; her daughter Sangeeta Shankar is also a leading player.

Also at the forefront of Indian violin playing is Dr Jyotsna Srikanth from Bangalore. Based in London, she plays both Carnatic classical music and various forms of folk, jazz and rock fusion.

A brief dip into Indian music quickly reveals that it is a deep and vast subject, its performance requiring great discipline and spiritual awareness. Consider this quote, next time you reach for a well-earned pint after scraping merrily through Old Joe Clark or Drowsy Maggie; 'The purpose of Indian music is to refine one's soul, discipline one's body, to make one aware of the infinite within one, to unite one's breath with that of space and one's vibrations with that of the cosmos.'

_____________________________________

The following article first appeared in FIDDLE ON magazine:

A Karnatic Violin workshop

I first met Dr Jyotsna Srikanth at the London Fiddle Convention in 2011, when she came along just to see what was happening, and introduced herself during the soundcheck. On hearing that she was a professional musician or considerable repute playing, among other things, a form of Indian-Jazz fusion, my interest was more than piqued. The same year we began rehearsing and performing together, my jazz and rock style creating an interesting contrast to her Karnatic (sometimes spelt Carnatic) Indian style. At the 2014 Convention Jyotsna not only performed in the evening concert, but also gave an hour- long workshop in the afternoon which I was lucky enough to be able to attend. A group of around 20 fiddlers were led through a fascinating and comprehensive introduction to the world of Karnatic music.

The earliest origins of Indian music lie in the Vedas- rhythmic chants addressed to the Hindu gods. Indian music today is divided into two principal regions; the northern (Hindustani) and the southern (Karnatic). This division occurred around 1000 years ago when the north became influenced by the Persians. The northern style is represented by the music of Ravi Shankar, and is perhaps better known to western audiences, but Jyotsna hails from Bangalore in the south, and she told us that the complex mathematical system of music here dates back over 2000 years.

The main principles of Karnatic music were set out around in the 16thC by the composer Purandaradasa, considered the “Grandfather” of South Indian music. He created a syllabus of exercises designed to introduce the student to the main features of raga and tala. Jyotsna explained how the violin was brought to India by bandsmen of the East India Company in Madras, during the Raj in the late 18thC. Local musicians immediately “saw the similarity and resemblance of the instrument with the human voice.” With some adaptations of style, the violin proved to be a perfect instrument for Indian music, and today it permeates every genre from classical to folk to Bollywood. It is an essential feature even of vocal concerts. The most obvious difference in playing style comes in the posture; the Indian violin is normally performed squatting on the floor, the violin held pointing down, anchored between the collarbone and the ankle of the right foot. This facilitates the “trump card`” of Indian music, the glissando, of which there are ten different kinds. The violin is tuned in two pairs of fifths. If the tonic is C, it will be CGCG; if in D it will be DADA. Scales The scale or raag is a series of notes which are followed by the melody line. In the Karnatic system there are 72 melakartas (“kings of the court”); also known as “major” scales, “parent scales” or janakas. These have all seven notes, both ascending and descending. Derived from these are “child scales”, in which one or more notes are missing- either ascending, descending or both. Since each parent can have many permutations of child scale, the total number of possible scales runs into the thousands. Each scale or raag has a name, and is associated with a particular mood, time of the day, season of the year, or even weather. Examples include Bhairav (early morning); D, Eb, F#, G, A, Bb, C#, D; Bhupali (late afternoon); D,E,F#, A, B,D; Malkauns (late night); D,F,G,Bb,C,D); and Miya Malhar (rainy season); D,E,F,G,A,B,C,C#,D) As with western modes, some raags are very popular, and have hundreds of compositions, whilst others exist more as little more than theoretical possibilities, and may only have a single composition. Rhythms The tala is the rhythm. This also can be very complex to western ears- 17, 19, 7 and a half…”but there is a simple method of counting and keeping rhythm, There is a method to do that. It is no rocket science!”

We all tried the Karnatic method of counting to 8 (the Adi Tala), clapping the hand and tapping fingers on the knee. The count goes; clap (1), little finger (2), ring finger (3), middle finger (4), clap (5), turn- a clap with the back of the hand (6), clap (7) and turn (8). The first four parts are called the laghu or count. The subsequent front and back of the hand are one “turn”; so you get to 8 with a count and two turns. You could reach nine with a “count” of five, and two turns. Or seven would be a count of three, and two turns. Simple? There are just 105 different rhythms or talas to learn, so nothing to get worried about.

A performance on Karnatic violin comes in three parts. The first is the Alap, a non-rhythmical improvisation of the particular scale or raga which has been chosen. Unlike in western music, there is no concept of chord changes, and the performance never deviates from the one scale. After the alap comes the composition (svarajati)- a fixed melody from an ancient repertoire of thousands. The bulk of the Karnatic compositions come from three composers from the 18th and 19thC; Tyagaraja, Dikshitar and Syama Sastri. Finally comes the kalpana svara (“creative notes”)- a rhythmic improvisation. This is the most exciting and challenging part of the performance, and Jyotsna then lead us through a series of exercises which would start us on the way towards this aspect of the music.

We practiced a number of scales, not only playing but also singing them. The seven notes of a “major” scale are named or numbered- a bit like do, re mi. In the Karnatic notation system (called sargam), the names are, ascending the scale, sa, ri, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni, sa. These names remain the same if the tonic is different, but they are not simply the numeric order in the scale. So if we are dealing with a pentatonic scale, the missing notes are removed from the naming system- for example sa, ri, ga, pa, ni, sa. (with the fourth and sixth missing). We were also briefly introduced to the language of percussionists, who name each type of beat with a different syllable, and are able to speak the name of each simultaneously with playing. It sounds something like ta-ki-ta, ta-ki-ta. Finally we ran up and down a number of different scales, starting with G, Ab, B,C,D, Eb, F#,G. This raga (Mayamalavagaula) is traditionally the first one taught to students. It is what we know in the west as the Hungarian gypsy scale; it is the symmetry of the fingering which makes it particularly suitable for beginners. We played this scale in various ways-doubling up the notes, adding some grace notes, and playing different patterns, both melodic and rhythmic, and trying some glissandos. It was a fascinating, comprehensive and authoritative workshop, and gave us the beginnings of an understanding of the complexity of this ancient and complex system of music. It was also an inspiration just to enjoy the beauty and elegance of the playing of such an expert as Dr Jyotsna Srikanth.

Links;

Chris Haigh is a freelance fiddler and writer based in London. He has worked with the leicester Based Bollywood band Diwana Arts, with S Harikumar, and with Jyotsna Srikanth's Bangalore Dreams. He has had several books published: Fiddling Around the World,Any Fool can Write Fiddle Tunes, (Spartan), The Fiddle Handbook (Backbeat/Hal Leonard) Exploring Jazz Violin (Schott), Discovering Rock Violin (Schott), Hungarian Fiddle Tunes (Schott), and Exploring Folk Fiddle (Schott).